A tale of two nations: demographic changes of China and India

Demographic changes spell new future for China and India

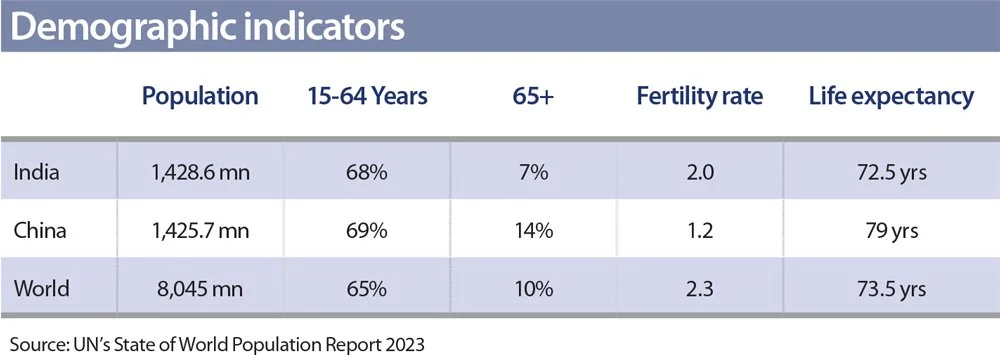

India’s population is expected to reach 1.4286 billion in mid-2023, outpacing China’s 1.4257 billion by around 3 million, according to projections by the United Nation’s State of the World Population Report 2023 published in April.

The two Asian giants combined account for over 35% of the world’s eight billion people. The US and Indonesia, the third and fourth most populous countries, lag far behind with 340 million and 282 million, respectively.

The UN report notes that China recorded its first year of negative growth in 2022 after decades of increases, and forecasts its population to drop to 1.3 billion by 2050 while India’s will surge to 1.7 billion.

Around 14% of China’s people are over 65 years old and the share will more than double by 2050, placing a burden on the existing workforce. Although Beijing ended its one-child policy in 2016 after 35 years, the fertility rate hasn’t improved and currently stands at 1.2 births per woman.

Meanwhile in India, only 7% of the population is older than 65 and the median age is only 28.4 years compared with 38.3 years in the US, 38.4 years in China, and 40.5 years in the UK. Although India’s fertility rate has also declined, it stands comfortably at two births per woman.

Major milestone

The demographic changes are a significant milestone for both China and India, marking the beginning of a new future for their national development.

China is entering into a new phase in which it can no longer leverage a massive and growing workforce to fuel future growth, which has been a key driver for its unprecedented economic rise in the past four decades. On the contrary, an ageing population will increasingly weigh on the nation’s resources. A new playbook is required for sustainable development.

Beijing is fully aware of this demographic change in the making and has been taking strategic measures to prepare for the eventuality. But the inflection point comes at a time when China is facing slow recovery after three years of Covid-19 lockdowns. Meanwhile, the US is leading an all-out campaign with its allies to contain China’s development on multiple fronts, exacerbating the challenges.

India, by contrast, is entering its new phase with lots of hope. Political stability under Prime Minister Narendra Modi over the past eight years has allowed monetary and fiscal policies to come together to support a wide range of economic reforms, remove structural rigidities, and make it easier to do business in the country.

India’s gross domestic product grew at an average annual rate of 6.79% over the past decade, reaching US$3.53 trillion in 2022 and overtaking the UK to become the fifth largest in the world after the US, China, Japan and Germany. Despite global uncertainties, India’s economy is expected to grow 6.9% this year, according to the World Bank’s forecast.

The Indian government has a unique opportunity to reap the rewards of its “demographic dividend”, putting the South Asian nation on course to become the world’s third largest economy by the end of this decade.

The concept

Governments traditionally juggle their population policies based on debates over having too many or too few people. The concept of the demographic dividend was introduced by Harvard economist David Bloom in the late 1990s to explain the economic growth that can result from changes in the age structure of a country’s population.

As fertility rates decline, there is a period of time when the working-age population, i.e., those aged 15-64, grows larger than the dependent population, i.e., children and the elderly. This creates a window of opportunity for a country to harness its young and productive workforce to drive economic growth, leading to increased productivity, greater savings and investment and increased per capita income, which in turn gives rise to higher standards of living and lower poverty.

Bloom attributed a large part of the rapid economic growth of East Asian countries from 1965 to 1990 to demographic shifts due to successful family planning programmes, which drove down fertility rates and population growth, thus boosting productivity.

But the demographic dividend only translates into economic acceleration if a government creates the right conditions to support growth.

China

When Mao Zedong established the modern day People’s Republic of China in 1949, its population growth rate was only 0.3% after a century of wars, epidemics, and famines. Mao believed a bigger population was crucial for nation-building, and encouraged families to have as many children as possible.

But a bigger population also means bigger problems for an underdeveloped economy. Rapid population growth put heavy strain on China’s scare resources and social services, dragging on the nation’s progress. Its population jumped 77% in just three decades, from 541 million in 1949 to 960 million in 1979, prompting Beijing to introduce the highly controversial one-child policy to prevent over-population.

In spite of the profound social and economic consequences, the policy also led to a demographic dividend phase in the following decades. Around the same time, the Chinese government implemented economic reforms and opened up the country to foreign investment and trade, invested heavily in education, infrastructure and technology, which created jobs and boosted productivity. The large domestic market also provided opportunities for businesses to grow and expand.

As a result, China’s economy grew at an average rate of 9% annually over the past four decades to $18.1 trillion in 2022, lifting more than 800 million people out of poverty.

India

India’s population has increased more than four-fold since its independence, from about 340 million in 1947 to 1.4286 billion today, at the rate of 15 million people per year. It entered the demographic dividend phase around 2010 when the share of the working-age population reached 51%. This can continue for another 20-25 years before the dependency ratio catches up.

However, India needs to address a number of deep structural problems in order to reap the rewards.

For one, without a vibrant large-scale manufacturing industry, it isn’t creating enough jobs for the young workforce. In his recent book on the employment crisis, Goutam Das, senior editor of India’s Business Today magazine, estimated that the economy has to create over a million new jobs each month in order to absorb demand for employment.

The jobless rate is persistently high, standing at 8.1% in April, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. For a country with a workforce of 500 million, this means over 40 million people are without jobs.

India also needs to address the fact that half of its graduates lack the skills to meet the demands of employers, according to global talent assessment firm Wheebox’s India Skills Report 2022. Educated unemployment has been a persistent issue for decades without significant improvement; unemployment rate soared from 3.6% at the matriculation level to 8% and 9.3% respectively, for graduates and postgraduates.

Then there is the fact that the proportion of women in the workforce is not only low but rapidly declining. The female labour participation rate plunged from 32% in 2005 to 19% in 2021, although many work in casual agricultural or domestic jobs. China, by contrast, has a female participation rate of 62%, a figure that is also far higher than the global average of 50%.

Lastly, the issue of brain drain is very serious. UN figures show that ten million mostly educated and skilled Indians migrated abroad over the past two decades.

India has the largest diaspora in the world. As of 2022, 18.68 million people of Indian origin and 13.45 million non-resident Indians live outside the country.

Challenges

The Modi government is stepping up efforts to create jobs through its flagship “Make in India” scheme to increase manufacturing growth and exports. It has attracted a number of large-scale electronics, auto components and textile firms to set up shop in India, joining the information technology, biotech, and pharmaceutical sectors to tap on the massive workforce. The nation is one of the beneficiaries of global supply-chain diversification as companies seek to reduce reliance on China as their sole manufacturing base.

To equip young Indians with market-relevant skills to be employable, a “Skill India” initiative was launched in 2015 and has trained around 60 million people to date.

India’s moment has come, but a lot more needs to be done to ensure that the nation can fully reap the rewards of its large population and not squander the opportunity.

Meanwhile, China needs to upskill its shrinking workforce to transition from labour-intensive into high-value manufacturing, services and technology sectors, and continue uplifting its population into the middle-income class so that they can “get rich before getting old”.

*This article was published in Asia Asset Management’s June 2023 magazine titled “A tale of two nations”.