Time for an Asian Monetary Fund?

Nations are reconsidering the downsides of depending on the US dollar

Back in 1997, Japan proposed the creation of an Asian Monetary Fund (AMF) to facilitate the region’s recovery from the Asian financial crisis. But the idea didn’t go anywhere because of strong opposition from the US on the grounds that it could undermine the International Monetary Fund (IMF). China was also reluctant to support it.

More than a quarter-century on, the notion of an AMF has come up again amid concerns about financial and economic security as the US increasingly makes use of the dollar to act unilaterally against adversaries.

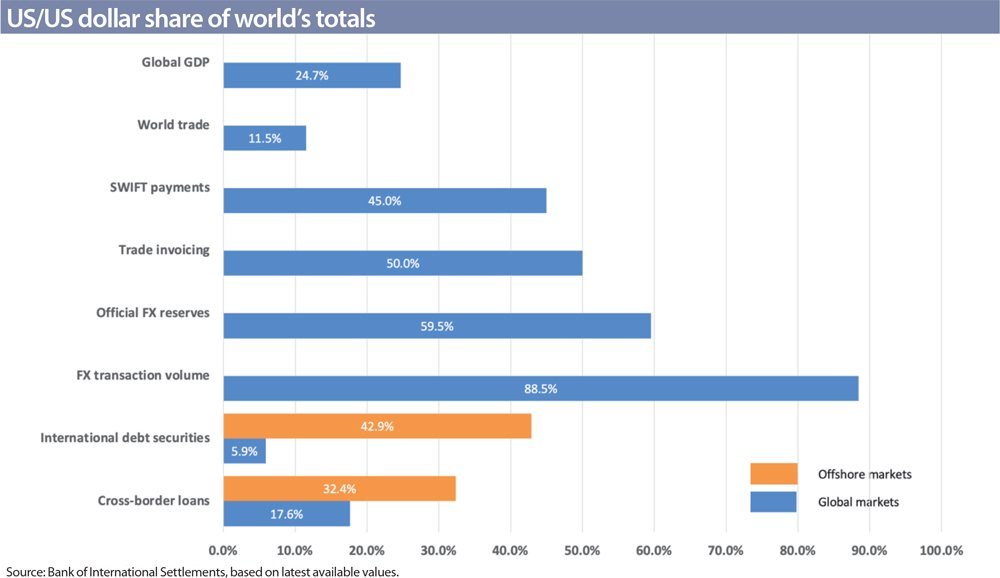

Developments such as the US seizure of Russia’s foreign currency reserves and barring Russia from using the SWIFT messaging system for international payments have prompted nations to reconsider the downsides of their monetary dependence on the US, and the existing unipolar international financial architecture centred on the dollar.

Countries which rely heavily on the dollar for their foreign trades have been suffering from the greenback’s rising strength since last year as the US Federal Reserve Bank hikes interest rates to rein in soaring inflation despite economic uncertainties globally.

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim resurrected the proposal for an AMF earlier this year.

“We cannot have the international infrastructure being decided by outsiders. We can work with them but we should have our own domestic, regional and Asian strength, not necessarily to compete but to have a buffer zone [against economic crises],” he said in his keynote address at a lecture in Bangkok organised by the Malaysian-Thai Chamber of Commerce on February 10. He believes the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, stands to gain substantial benefits from an AMF that also includes China, Japan and South Korea.

There is a similar regional institution in the Middle East. The Arab Monetary Fund, which currently has 22 member states from the Middle East and Northern Africa, was founded in 1976 as a sub-organisation of the Arab League. It provides financial support for members’ emergency needs and promotes economic development in Arab countries.

Cautious response

Anwar, who went on an official visit to China in March, said he raised the idea of forming the AMF to President Xi Jinping. According to him, the Chinese president welcomed further discussions on establishing the institution.

“There is no reason for Malaysia to continue depending on the dollar,” Anwar told the Malaysian parliament after his China visit. He also said the Malaysian central bank is working with its Chinese counterpart for the two nations to settle trades using the Malaysian ringgit and Chinese yuan.

Response from other nations has been cautious. Some critics saw the proposal as Anwar’s attempt to curry favour from Beijing to bolster his leadership position in Malaysia.

Indonesia’s Economic Minister Airlangga Hartarto said in an interview with The Jakarta Post on April 11 that while the idea of AMF was good for the region, commitments from nations may be hard to come by.

“First, there have to be countries committed to funding it. So, we can’t just talk about [forming] the institution directly,” he said. “Even the existing institution, the IMF, has many challenges.”

The IMF and the World Bank were founded at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944 at the end of World War II. The World Bank’s mission is to work with developing countries to reduce poverty and increase shared prosperity, while the IMF serves as a watchdog of the monetary and exchange rate policies vital to global markets.

But the IMF lost its primary purpose when the US abandoned the gold standard in the early 1970s to form today’s international financial system based on floating exchange rates. Since then, the IMF has been active in providing resources to countries in economic crisis, and delivery of technical assistance and financial services.

The IMF regularly draws criticism for attaching very harsh conditions to its bailout packages. They often involve drastic spending cuts, tax increases, mass unemployment, and other structural adjustments that ignore ground-level realities. Critics have accused the IMF of impoverishing bailout recipients in a number of cases.

Countries such as Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand which turned to the IMF during the Asian financial crisis have painful memories of the hardship they suffered in order to meet loan conditions.

The IMF is ultimately controlled by the US. Although Asia, excluding Japan, collectively holds 21.85% of the votes in the IMF and the US holds just 16.5%, any change in the control structure requires the backing of 85% of votes. This means the US has effective veto power.

The challenges

An AMF owned by Asian countries, for Asian countries, should have better understanding of the region’s economies and cultures and would be more sensitive to the needs of the nations. But there are formidable challenges in turning the idea into reality.

For one, the difficulties of getting potential members’ agreement on how to finance the institution and the terms on which the funds will be made available to those in need should not be underestimated. It involves not only financial issues but also a geopolitical game of thrones among the Asian powers.

For another, limited resources and expertise would probably confine the AMF to providing stop-gap assistance for members’ emergency needs, at least initially, requiring the IMF to step in for longer-term solutions. This means the AMF won’t be operating without IMF influence.

Then there is the question of establishing the AMF’s reserve currency architecture. It will be very complicated. Replacing the US dollar with a currency such as the Chinese yuan or the Japanese yen would not significantly benefit smaller trading nations in Asia.

The AMF’s goal should be to issue its own special drawing rights or SDRs for participating central banks to hold as part of their reserves, which could be exchanged for any currency from the fund for an emergency situation. But the IMF’s experience with SDRs shows that this will only marginally reduce dependency on the US dollar.

IMF SDRs now account for just 2% of global central banks’ reserves, pointing to what is likely to happen with AMF SDRs, since Asian central banks would rather hold US Treasuries or other sovereign assets for liquidity and investment returns.

US opposition sank the idea of an AMF 26 years ago. It would be naïve to think that it will be any easier this time around given the intense rivalry between the US and China.

Moreover, most Asian nations are unwilling to upset their balancing act between the two superpowers by antagonising either one – and potentially losing the benefits of the relationship. It’s hard to foresee that the current discussions on AMF will materialise any time soon.

On the brighter side, the failed AMF proposal in 1997 helped lead to the establishment three years later of the Chiang Mai Initiative, a regional multi-currency swap arrangement allowing the ASEAN nations plus China, Japan and South Korea to address short-term dollar liquidity needs by swapping local currency for US dollars when required. It was recently broadened to include the use of other currencies, including the yuan and the yen, on a voluntary basis.

The size of the facility has grown to US$380 billion even though there hasn’t yet been a need to draw on it.

Bypassing the dollar

Meanwhile, concerns about the US dollar’s dominance have triggered the emergence of a number of agreements globally on wider invoicing and the settlement of commercial transactions in other currencies.

China is already settling bilateral trades with Russia, Iran and North Korea in each other’s currencies without involving the dollar. It is reportedly planning to do the same with Brazil and South Africa too.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have been talking about settling oil trades in the currencies of partner countries. And the Arab Monetary Fund has proposed alternative payment systems to bypass SWIFT.

The Indian Ministry of External Affairs recently announced that trade between India and Malaysia can be settled in Indian rupees. China and Malaysia may have a similar deal if their discussions prove fruitful.

At their meeting in Bali in late March, ASEAN finance ministers and central bank governors discussed the increased use of local currencies for trade settlement to reduce reliance on major foreign currencies.

These moves will accelerate the pace of de-dollarisation and pave the way for the transition from a unipolar financial system based on the dollar to a more multipolar financial system. But don’t expect the dollar hegemony to collapse any time soon. Rome wasn’t built in a day.

*This article was published in Asia Asset Management’s May 2023 magazine under the same title.