Evolution of the securities services industry

M&A activities play a major role in shaping the securities services industry in Asia

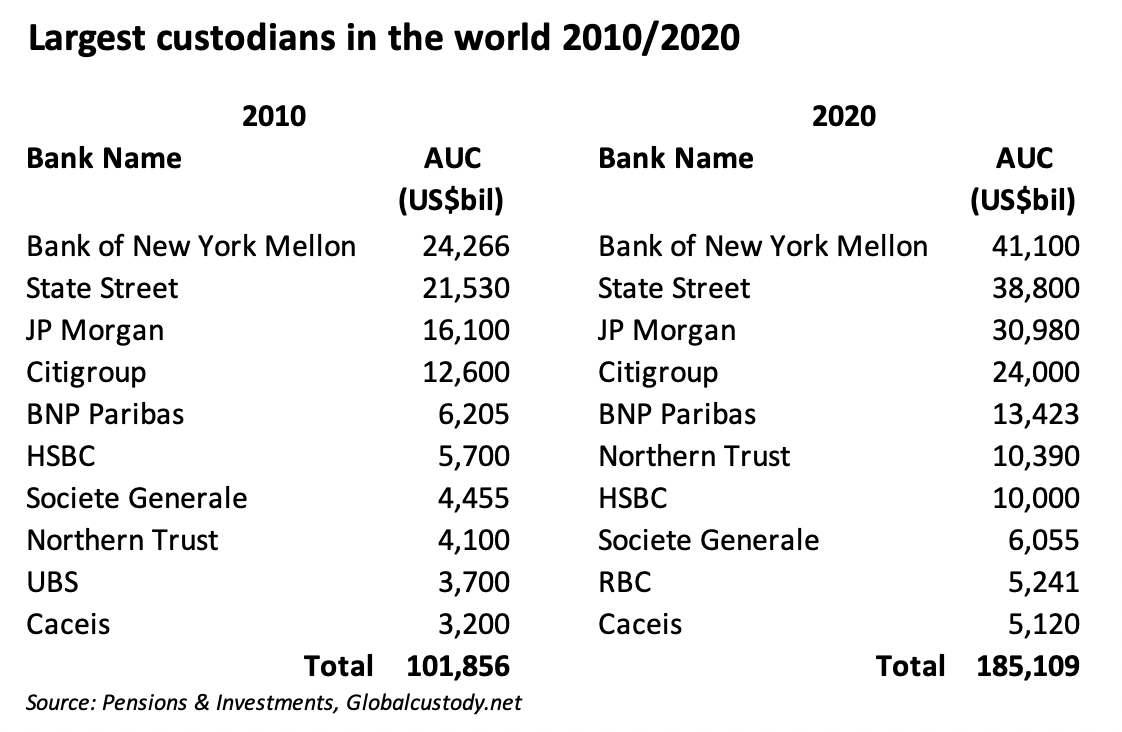

The custodian industry is highly concentrated today, with 60% of the assets held by the top five custodians, the result of several decades of growth and consolidation.

The US Employees Income and Retirement Savings Act of 1974 required companies to appoint independent trustees and depositories for their employee retirement plans to ensure they are operated in the best interest of pension holders. That was the trigger for the custodian industry to take off. US money-centre banks raced to set up custody businesses to grab a piece of the market, as did banks in the UK and Canada, which also had sizeable pensions industries.

In the late 80s and early 90s, global players such as Chase Manhattan, Morgan Guaranty Trust, Bankers Trust, State Street, Morgan Stanley and Barclays set up shop in Asia to expand their coverage. HSBC, Standard Chartered and Citibank also established extensive local custody operations across the region.

But after over a decade, the allure of the business began to fade. The market had become crowded, and without the right scale, margins were not as attractive as for other business lines.

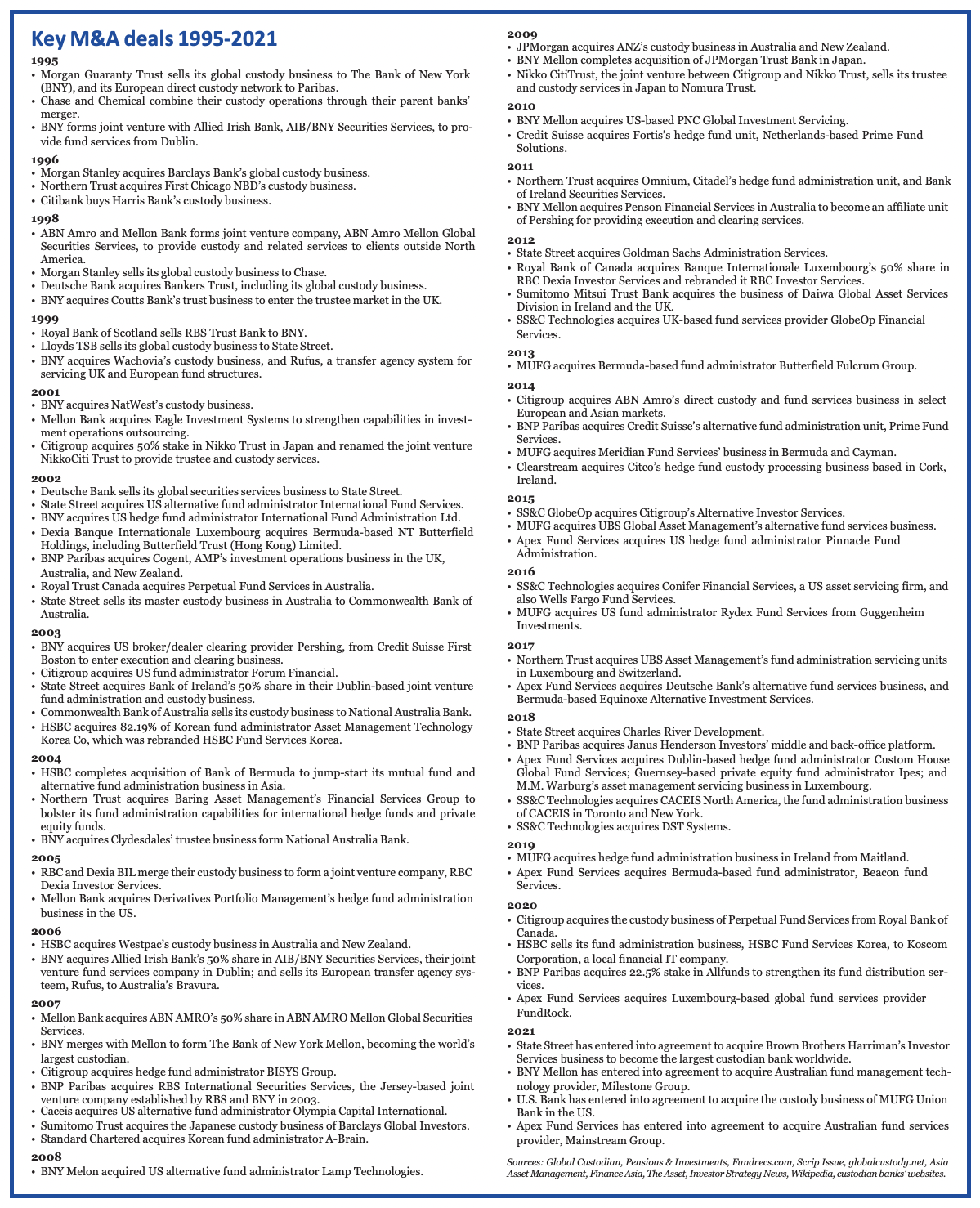

The first high profile exit came in 1995. Morgan Guaranty Trust, which was also the operator of Euroclear at the time, felt that it had too many business lines and wanted to focus only on those that could be among the top three globally. Even though Morgan concluded that the custody business could be among the top three, it would require very substantial investments to revamp the technology platform and infrastructure.

On hindsight, Morgan’s sale of its custody business was not its best decision. The firm lost huge amounts of liquidity and capital market flows. The Bank of New York (BNY) and France’s Paribas became the beneficiaries. BNY transformed from a local custodian in the US market to become a top global custodian, and Paribas got a superb European sub-custody network to build on. More importantly, both onboarded entire teams of talented people to be pillars of their business, some of whom are still with the firms today.

Still, Morgan’s departure prompted other players to re-consider their own involvement in the business. Since then, many other key names, such as Morgan Stanley, Bankers Trust, Barclays, NatWest, Lloyds and RBS Trust, have also exited the custody business.

In the meantime, the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999, which had separated commercial banking and investment banking in the US for more than half a century, also kickstarted a wave of bank consolidations, which led to more custody players disappearing.

JP Morgan Chase is a case in point. The investment banking group is the product of a long list of mergers and acquisitions over a decade, involving Chemical, Manufacturers Hanover, Chase Manhattan, First Chicago, National Bank of Detroit and Bank One, turning it into a financial powerhouse and also enabling it to get back into the securities services business.

Deutsche Bank acquired Bankers Trust in 1998 to pursue its ambition in investment banking, a move that also got it into the securities services business. But the German lender eventually sold the business to State Street Corporation in 2002.

For players staying in the game, the critical goal was to attain business scale and geographical footprint quickly. This was a key driver for the M&A activities that followed.

BNY, for example, made over 30 acquisitions after Morgan, before its eventual merger with Mellon Bank in 2006 to become the largest custodian at that time. State Street also swallowed the global custody businesses of Lloyds and Deutsche Bank and strongly bolstered its position globally.

New capabilities

The M&As were also driven by the need to acquire new capabilities to supplement core custody to meet the evolving needs of asset owners and investment managers. The alternative space was targeted for mergers because asset owners were allocating more to non-mainstream investments to enhance returns, while investment managers were venturing into it to complement their strengths in traditional assets to protect their client relationships.

State Street was among the first movers to offer a credible service offering in alternatives by acquiring International Fund Services in 2002. It built on this with more deals to become one of the largest alternatives fund administrators. The following years saw transactions in this space by every major player.

Apart from independent administrators, many large investment banks, including Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Citigroup, UBS, Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank, have set up dedicated prime brokerage business units to service hedge funds. Several of these prime brokers also provided fund administration services to their hedge fund clients as a one-stop shop.

But as hedge funds and traditional funds converged, margins began to decline. Some of the banks then decided to concentrate on their core competencies and sold their hedge fund administration to custodian banks. State Street picked up the hedge fund administration unit from Goldman Sachs, Northern Trust from Citadel, BNP Paribas from Credit Suisse, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG) from UBS, and SS&C Technologies from Citigroup.

There have been two major deals in the area of investment operations outsourcing in the last two decades. State Street made a splash in 2018 by acquiring Charles River Development to form the centrepiece of its Alpha platform for front-to-back outsourcing. This created the battleground for a new wave of outsourcing deals aligning the front-office’s order management system to the middle and back-office operations so that data can be kept consistent end-to-end throughout the organisation and enriched with analytics for delivery to where they are needed for investment decisions.

Mellon Bank was in fact the pioneer in this area with its acquisition of Eagle Investment Systems back in 2001 to provide an integrated operational model for outsourcing. Eagle helped Mellon – and later BNY Mellon – to add clients, being a core part of the bank’s outsourcing model and its data strategy.

It did not attract as much attention as State Street’s acquisition of Charles River, probably because outsourcing was at the time still a new idea to investment managers, who were more keen to unload their costs to custodians through back-office lift-outs and outsourcing selective middle-office functions.

Newcomers

Despite a number of high-profile exits, there was no shortage of newcomers to the industry, including the likes of ABN Amro, Fortis, and Dexia Banque Internationale Luxembourg. But without a big home base market like their US counterparts, many failed to gain a significant foothold in the market and have left the industry.

ABN Amro, which is today operating operating a direct custody and clearing network across different time zones, was formed from the merger between Alegemene Bank Netherland and Amro Bank in 1991. The banking group expanded globally and embarked on a series of M&A activities during the following two decades, until it was embroiled in almost a decade of chaotic disruptions, including takeover by the consortium of Royal Bank of Scotland, Fortis and Santander, breaking up into parts, nationalisation, delisting, and re-listing again into its current form.

ABN Amro entered into global custody in 1998 by forming a joint venture company, ABN Amro Mellon Global Securities Services, with Mellon Bank to provide services to clients outside North America. It was among the top 10 custodians in the world during the early 2000s, but eventually sold its 50% share in the joint venture to Mellon Bank in 2007. Citigroup also picked up direct custody business in a number of European and Asian markets when ABN Amro put them up for sale in 2014.

Paris-based BNP Paribas is the result of a merger between commercial bank Banque Nationale de Paris and investment bank Paribas in 2000. It’s the only non-US player among the five largest custodians in the world. After successfully solidifying the direct custody business in Europe, it acquired Cogent’s fund operations from AMP in 2002 and RBS International Securities Services in 2007 to enter fund services and global custody.

Over the last ten years, BNP Paribas expanded into Asia and the Americas to complete its global strategy, including acquiring Credit Suisse’s business unit for alternative funds, and Janus Henderson Investors’ middle and back-office platform for US mutual funds to strengthen its product depth. Operating on a global/local business model, it provides multi-asset class solutions for both buy-side and sell-side clients.

Although the custodian industry is top heavy, there is still room for new entrants in specialist areas of the ecosystem. SS&C Technologies, a Connecticut-based investment management software provider, bought the UK’s GlobeOp Financial Services in 2012 and then broke into the alternative fund administration space by acquiring Citigroup’s Alternative Investor Services in 2015. Building on this acquisition with several other deals, it’s now the largest alternative fund administrator worldwide.

MUFG Investor Services, a subsidiary of Japan’s MUFG, has made a string of acquisitions since 2013 and is now one of the ten largest alternative fund administrators in the world with a global presence.

Meanwhile, Bermuda-registered and private equity-backed Apex Group has been on a shopping spree since 2015 to assemble a range of service capabilities, including fund administration, middle office, custody, depositary, private equity, hedge funds, and corporate services. It now boasts 50 offices worldwide with 5,000 employees.

Australia

In Asia Pacific, Australia has had some colourful securities services M&A activities over the last 20 years. Its superannuation fund industry started in 1986 with the birth of the first super fund, Award Super. The industry’s growth encouraged local banks to establish custody operations, and also attracted foreign fund managers and custodians to set up shop in Australia.

But the fun ride came to an end in the early 2000s when players which did not like the relatively low margins of the custody business decided to exit. The list includes AMP’s Cogent, which sold its business to BNP Paribas, ANZ to JPMorgan Chase, Westpac to HSBC, and Perpetual to Royal Bank of Canada, which recently sold the business to Citigroup.

Although State Street was the first provider to introduce master custody in Australia, it sold the business to Commonwealth Bank in 2002, which sold it to National Australia Bank (NAB) a year later. But State Street re-entered the market several years later.

NAB has had a domestic custody business for many decades. At one point, it extended its footprint to the UK when the parent bank acquired Glasgow-based Clydesdale Bank in 1987, including its local custody business. But NAB Group struggled to unlock value from the acquisition and the two banks de-merged in 2015.

When master custody was introduced in Australia in the mid-1980s, NAB’s custody business came to life. In 1996, it appointed BNY as its exclusive global custodian to offer master custody solutions to super funds. By the late 1990s, it became the largest provider in Australia.

Despite the success, the parent group has made several attempts to sell the business over the past two decades, including several negotiations with BNY/BNY Mellon and JPMorgan Chase. But none of these discussions came to fruition. In 2015, it terminated its long-standing partnership with BNY Mellon and appointed Citibank as global custodian.

NAB’s lack of commitment in the business has caused a sharp decline in client confidence. Even though it is now the only noteworthy local custody player left in Australia, its market share is dwindling quickly.

Rest of Asia Pacific

Pure securities services M&A deals have been few and far between in the rest of the Asia Pacific region, which is highly fragmented, with each country having its own idiosyncrasies and regulatory restrictions. Asian custodian banks are mainly focused on their domestic markets.

Singapore’s DBS Bank is the only Asian lender that has developed a modest regional custody footprint on the back of its parent group’s regional expansion. It currently provides direct custody in five Asian markets. But it’s far behind the networks of HSBC, Standard Chartered and Citibank in the region.

Most mergers of custody operations in Asia occurred as a result of consolidation by their parent banking groups, such as the formation of a handful of mega trust banks in Japan.

The most significant transaction was HSBC’s acquisition of Bank of Bermuda’s fund servicing business in Hong Kong in 2004. This enabled HSBC to jump-start its regional business in mutual fund and alternative fund services to become the largest provider in Asia today, supplementing its dominant local custody network.

There have been several small deals by HSBC, Citigroup, Standard Chartered and BNY Mellon in their bid to break into Japan and South Korea, but none of them have produced significant results. China, meanwhile, has not allowed voluntary bank mergers thus far.

M&A activities have played a major role in shaping the custody industry’s landscape over the past quarter century. The industry is now entering into the digital age. Technological, regulatory, and economic disruptions will accelerate alongside developments in digitalisation, artificial intelligence, big data, and digital assets.

Some incumbent players will find it hard to remain in the game; Brown Brothers Harriman’s sale of its business to State Street is just the first of its kind. But as in the past, new players will continue to come in with new ambitions, new energy, and new ideas. The involvement of private equity firms and participation by technology firms will become increasingly influential in reshaping the competitive landscape in future.

*This article was published in Asia Asset Management’s 25+ Anniversary Special Edition in December 2021 titled “Industry in flux” .